Enshittification is a phenomenon we are all aware of. Even if you’ve never heard the term, its feeling is universal to anyone using the internet. If you’ve seen Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, and even Substack copy TikTok’s short-form video success, you know what it is. If you’ve seen platforms shove large language models like ChatGPT shoved into our faces, usability and accuracy be damned, you know what it is. If you’ve seen Netflix, once a novel, valuable product, devolve into a pathetic library of mass-produced, bland content meant to be consumed while you scroll on your phone, all while dozens of imitators beg for your attention and subscription revenue, you know what it is.

Put simply, enshittification is the gradual decay in the quality of internet platforms driven by the all-consuming profit motive. It is a ceaseless drive towards sameness and mass appeal. It rejects niche in favor of reach, because niche is inherently limited. Instead, platforms want to be a one-stop shop for anything you might want to do online, and thus slowly morph into the same version each other marketed towards slightly different audiences.1

The sameness of enshittification is just one symptom of the larger paradox of western culture, which encourages difference and individuality. But just as enshittification is a shallow manifestation of sameness, so too our difference is shallow—it is the media we consume, the experiences we post to social media, the career path we choose and the successes we achieve along the way. It is our consumer profiles that Google builds from our browser history, the personas gleaned from social media algorithms zeroing in on what keeps us on their apps longer. Our difference is quantified, commodified, flattened into economic and digital contexts. We must buy into this hollow difference, because if we don’t, that means we might develop solidarity with our fellow humans and upset the ruling order.

Embracing indifference, therefore, is a radical act.

The word indifferent ("unbiased, impartial, not preferring one to the other") comes from the latin indifferentem ("not differing, not particular, of no consequence, neither good nor evil"). It means recognition of the sameness between us and our fellow humans, and indeed the sameness between us and what Lao Tzu calls the “ten thousand things” (the material world/universe). We are the same as a tall redwood tree and the soil from which it grows. We are the same as a lion and the gazelle it hunts. We are the same as the deep sea and the phytoplankton within its waters. We are the same as the barren moon and the stars beyond it.

Being indifferent doesn’t mean we ignore the wildly different material conditions that some of us experience. It is not being “color-blind” or using our shared humanity to join the “all lives matter” or “men’s rights” camps. It simply means recognizing that underneath all the inequality is a oneness that, if tapped into, can unite us. It means solidarity across ethnicity, geography, religion and culture; it is Fred Hampton’s Rainbow Coalition.

Indifference rejects neoliberalism’s power over us, power exerted through the exploitation of our difference. Byung-Chul Han remarks on this “positive power” in Psychopolitics, “The negativity of otherness or foreignness is de-interiorized and transformed into the positivity of communicable and consumable difference: ‘diversity’.”

What neoliberalism leads to is not freedom but isolation.

In this post, I will examine the theme of indifference in verse #5 of the Tao Te Ching, and how we can apply its message to the modern necessity for solidarity in the face of fascism. Here is the verse in full:

Heaven and earth aren’t humane. To them the ten thousand things are straw dogs. Wise souls aren’t humane. To them the hundred families are straw dogs. Heaven and earth act as a bellows: Empty yet structured, it moves, inexhaustibly giving.

Verse #5 builds on the theme of emptiness which I wrote about in my analysis of verse #4, yet it goes further by challenging us to unpack another statement that goes against the grain: “wise souls aren’t humane.” Spicy take, no? Let’s jump in.

Heaven and earth aren’t humane. To them the ten thousand things are straw dogs.

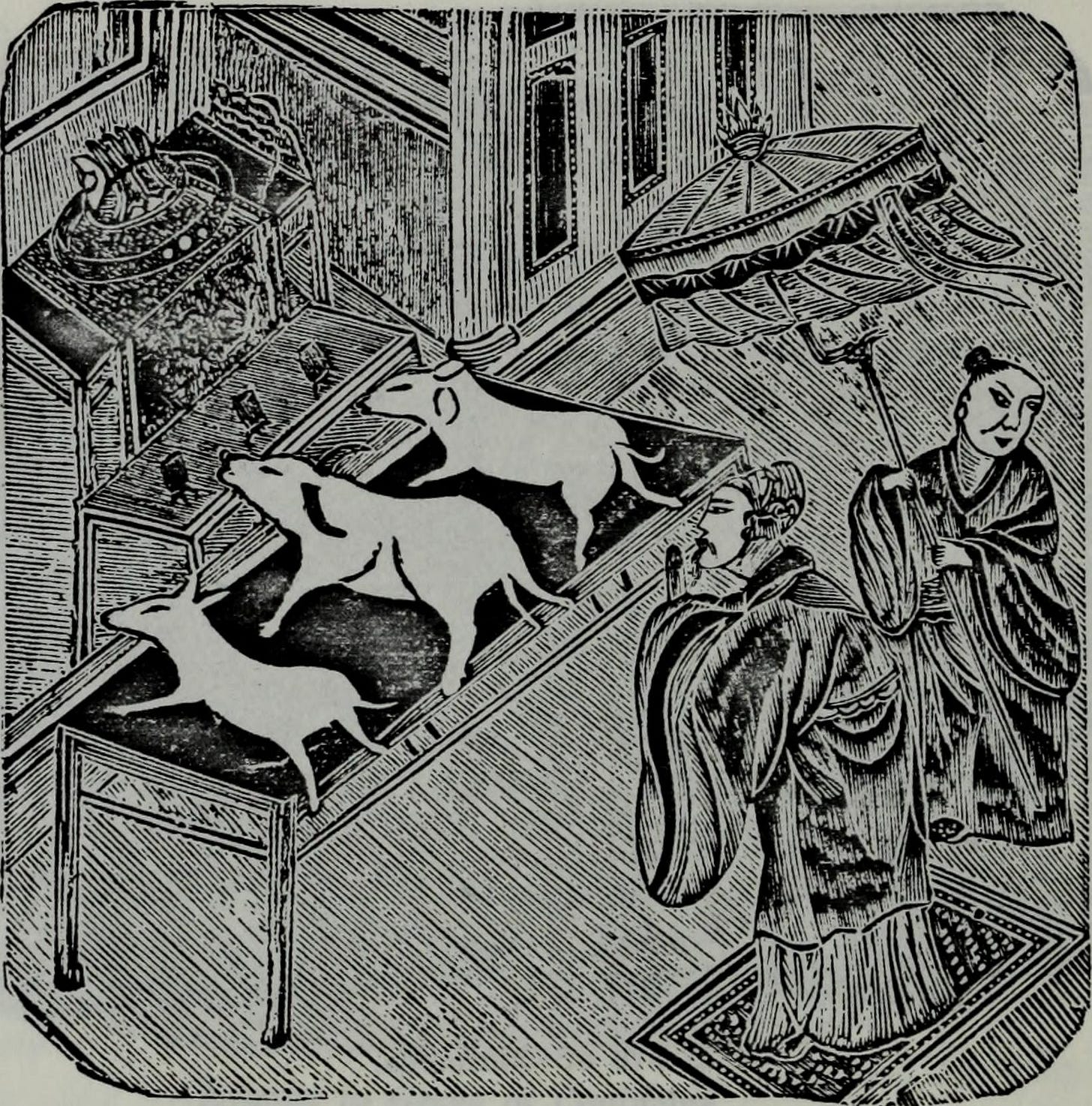

Straw dogs (芻狗; chú gǒu) or grass dogs were used as ceremonial objects in ancient China as a replacement for the sacrifice of living dogs. Zhuangzi describes their ceremonial use as such:2

Before the grass-dogs [芻狗 chú gǒu] are set forth (at the sacrifice), they are deposited in a box or basket, and wrapt up with elegantly embroidered cloths, while the representative of the dead and the officer of prayer prepare themselves by fasting to present them. After they have been set forth, however, passers-by trample on their heads and backs, and the grass-cutters take and burn them in cooking. That is all they are good for.

Comparing the ten thousand things (the material universe) to straw dogs in the eyes of Heaven and Earth, thus, has several meanings. Primarily, it indicates their impartiality, even indifference, towards the material world. “Heaven and Earth” are repeatedly mentioned in the Tao Te Ching, particularly in Le Guin’s translation, so I think it’s appropriate we unpack this.

It should be implied but it bears repeating: Lao Tzu’s “heaven” has nothing to do with the heaven of Abrahamic religions. In his translation, Stephen Mitchell, perhaps wanting to use language without this baggage for his western audience, completely removes any mention of “heaven,” instead opting for “sky” or “universe,” and opts for “infinite worlds” or “Tao” over “heaven and earth.” Not only does Mitchell’s translation lose the YinYang duality of heaven and earth, but in replacing “heaven and earth” with “Tao,” he does a disservice to both terms. The Tao contains the totality of heaven and earth, but they are not the same thing.

In ch. 25, Lao Tzu describes the Tao as “Something mysteriously formed, / Born before heaven and Earth,” and later, that “Man follows Earth. / Earth follows heaven. / Heaven follows the Tao. / Tao follows what is natural.”3 Heaven creates and Earth receives, Heaven is the father and Earth the mother. Together they birthed man, not in the sense that an omnipotent God would, but in the sense that Heaven and Earth are nature, and nature creates all things.

Thus, the indifference of Heaven and Earth towards their creation, the material world, the ten thousand things, is the same as nature’s indifference. Ch. 42 says, “The ten thousand things carry yin [earth] and embrace yang [heaven]. They achieve harmony by combining these forces.”4

Nature doesn’t choose sides, and it is not cruel nor kind. Sue Ch’e says,5

Heaven and Earth aren't partial. They don't kill living things out of cruelty or give them birth out of kindness. We do the same when we make straw dogs to use in sacrifices. We dress them up and put them on the altar, but not because we love them. And when the ceremony is over, we throw them into the street, but not because we hate them. This is how the sage treats the people.

This transitions us nicely into the rest of the verse.

Wise souls aren’t humane. To them the hundred families are straw dogs. Heaven and earth act as a bellows: Empty yet structured, it moves, inexhaustibly giving.

The attitude of wise souls towards their people sounds, at first, quite harsh. Treating them like nothing more than straw dogs, to be used and tossed away once their purpose is fulfilled. But if we examine this line in relation to the verse, and quotes I’ve pulled in thus far, it begins to come into focus.

Wise souls, in this verse, are likened to Heaven and Earth; they are impartial and indifferent. They are both described as inhumane, but not cruel, because as Le Guin writes in the notes to this chapter, “cruelty is a human characteristic […] you can only be kind and cruel if you have, and cherish, a self.”

Lao Tzu likens heaven and earth—and, we can infer, wise souls—to a bellows, which contains the quality of emptiness. Wang P’Ang says, “A bellows is empty so that it can respond to things. Something moves, and it responds. It responds but retains nothing. Like Heaven and Earth in regard to the ten thousand things or the sage in regard to the people, it responds with what fits. It isn't tied to the present or attached to the past.”

To be indifferent is to be inexhaustible. It is effortlessness, which Byung Chul Han writes is the Far Eastern counterpart to the Western concept of freedom. “You are effortless when you do not set anything against the world. When you fully unite with it.”6 The unification with nature, in my view, is the core of wu wei [effortless action]. Wu wei means working with the flow of nature to move through the world organically. Our subjugation of nature, our destruction of ecology and our domination of the environment, means that it pushes back against us, leading to our exhaustion. Nature is inexhaustible, and humans are not. It will continue to wear us out until we accept the world as it is and operate within its confines, or push ourselves to the point of total annihilation.

The way we respond to humanity’s hyperactivity, activity that is driving us towards disaster, should not be with activity for activity’s sake. Philosopher Slavoj Zizek wrote the following in a recent Substack post (which is free and a good read):7

The endless emphasis on the necessity to act, to do something, betrays the subjective stance of not doing anything. The more we talk about the impending ecological catastrophe, the less we are ready to do. Against such an interpassive mode, in which we are active all the time to make sure that nothing will really change, the first truly critical step is to withdraw into passivity and refuse to participate. This first step clears the ground for true activity, for an act that will effectively change the coordinates of the constellation.

To follow the Way is not a conscious altruism, it is a natural selflessness. To be selfless is to recognize that the self is an illusion. To be altruistic is to act out of a superficial, performative care for others that might make you feel better but doesn’t produce true goodness in the world. Le Guin writes, “Altruism is the other side of egoism. Followers of the Way, like forces of nature, act selflessly.”

Taking verse #5 to heart leads us to question the motives for our supposed good deeds. If we have good hearts, perhaps it is best to listen to those hearts rather than do what might appear to be helping, or what might signal our virtue to others. Rather than constant communication, maybe we should shut the fuck up and listen. Sung Ch’ang-Hsing says, "If our mouth doesn't talk too much, our spirit stays in our heart. If our ears don't hear too much, our essence stays in our genitals. In the course of time, essence becomes breath, breath becomes spirit, and spirit returns to emptiness.”8

In letting go of the desire to be seen as virtuous, we also realize that we are more similar to those we look down upon than we’d like to admit. This is what Siddhartha realizes towards the end of his journey in Herman Hesse’s Siddhartha. After a lifetime of suffering, asceticism, indulgence, and spiritual malaise, he finally wakes up to the reality that he is no better than those he once dismissed as “child people.”

He looked at people differently than he did before, less cleverly, less proudly, and thus with greater warmth, with greater curiosity, engaging more with them [...] These people did not seem alien to him as they once did […] It still seemed to him these child people were his brothers; their vanity, covetousness, and ludicrousness had lost their absurdity for him, had become comprehensible, lovable, even worthy of esteem. A mother's blind love for her child, an educated father's blind pride in his only little son, an idle young woman's blind and frantic pursuit of jewels and the admiring eyes of men, all these impulses, all these childish matters, all these simple, foolhardy or monstrously strong, extremely vivid, strongly opposing drives and desires were no longer childish things for Siddhartha now; he saw people live for their sake, saw them accomplish infinitely difficult tasks for their sake, make journeys, wage war, suffer endlessly, endure endlessly, and he could love them for that.

This solidarity is something we lose sight of too often. We paint those we disagree with as markedly different from us, as lesser-than. Leftists will talk about how we are conditioned into an imperialist, white supremacist, capitalist patriarchy (which is true; s/o bell hooks), then turn around and act surprised when this conditioning is reflected back at them. When we treat the “other” with haughty dismissal, is it any wonder that they feel attacked, condescended to or alienated from our cause?

Fire is best fought with water, not with more fire9; hate is best fought with love, not with more hate; arrogance is best fought with empathy, not with more arrogance. To be indifferent means to understand that we are all in this together, and the ignorance of our “enemies” cannot change the fact that they are human, too.

The Book of Chuang Tzu (ch. 14)

Ch. 25, Gia-fu Feng translation

Ch. 42, Gia-fu Feng translation

Lao-tzu’s Taoteching, translated by Red Pine with selected commentaries of the past 2000 years

Absence by Byung-Chul Han, p. 62

Lao-tzu’s Taoteching, translated by Red Pine with selected commentaries of the past 2000 years

“We don’t think you fight fire with fire best; we think you fight fire with water best. We’re going to fight racism not with racism, but we’re going to fight with solidarity. We say we’re not going to fight capitalism with black capitalism, but we’re going to fight it with socialism. We’re stood up and said we’re not going to fight reactionary pigs and reactionary state’s attorneys like this and reactionary state’s attorneys like Hanrahan with any other reactions on our part. We’re going to fight their reactions with all of us people getting together and having an international proletarian revolution.” - Fred Hampton

such an interesting read! it reflects a lot of what i’ve been thinking about the last six months or so after dealing with massive burnout. how we as leftists seem to have less compassion out of a need to appear more radical.

i also recently watched a video about how religious goals and tools are so often built around men, and why they fall flat for people of marginalized genders. would love to hear your thoughts on it! the presenter is speaking in binary terms but i think the point remains! https://youtu.be/ZMnF32GlWss?si=p1OfviCk-uORroUH

thanks as always :)