There’s an well-known saying in China by the Confucionist Tung Chung-shu (179-104 B.C.), “Heaven changeth not; likewise the Tao changeth not.” Mao criticized this aphorism as dogmatic in his essay On Contradiction, saying it was co-opted by the “decadent feudal ruling class” as a means of justifying their oppression.1 If things are static and unchanging, then the underclasses simply must accept the way things are and not resist.

The Tao is described as many things in Tao Te Ching—eternal, infinite, great, divine, elusive, intangible, impartial, the source of the Ten Thousand Things, mother of heaven and earth. The closest thing we get to “static” is Stephen Mitchell’s translation: “Since before time and space were, the Tao is. It is beyond is and is not.”

Tung’s mischaracterization of the Tao was convenient, as it legitimated Confucionist social hierarchy, feudal domination and oppression, and the expansion of the Chinese empire. But Mao confoundingly applies this quote to all metaphysics.

The metaphysical or vulgar evolutionist world outlook sees things as isolated, static and one-sided. It regards all things in the universe, their forms and their species, as eternally isolated from one another and immutable.

He advocates instead for dialectical materialism, a concept drawn from Marxism, as a means of understanding the world. Let’s break that down.

Essentially, (historical) materialism means that the material events in history, the economic and social factors that lead to our ever-evolving society, are more important than any ideals. One example that helped me understand this is the American Revolution. An idealistic perspective would say that the ideals set forth by the founding fathers—freedom, equality, and justice for all—led to their revolt, but Marx would say the material contradiction between the exploited colony and its ruling British empire were more impactful.

Dialectics is a complex concept that has different iterations depending on the thinker. Essentially, it is a process of finding truth by examining oppositional forces. The Socratic method written about in Plato’s Dialogues, in which Socrates and others would develop and refine a definition of something like truth or beauty through conversation, could be thought of as an early form of dialectics.

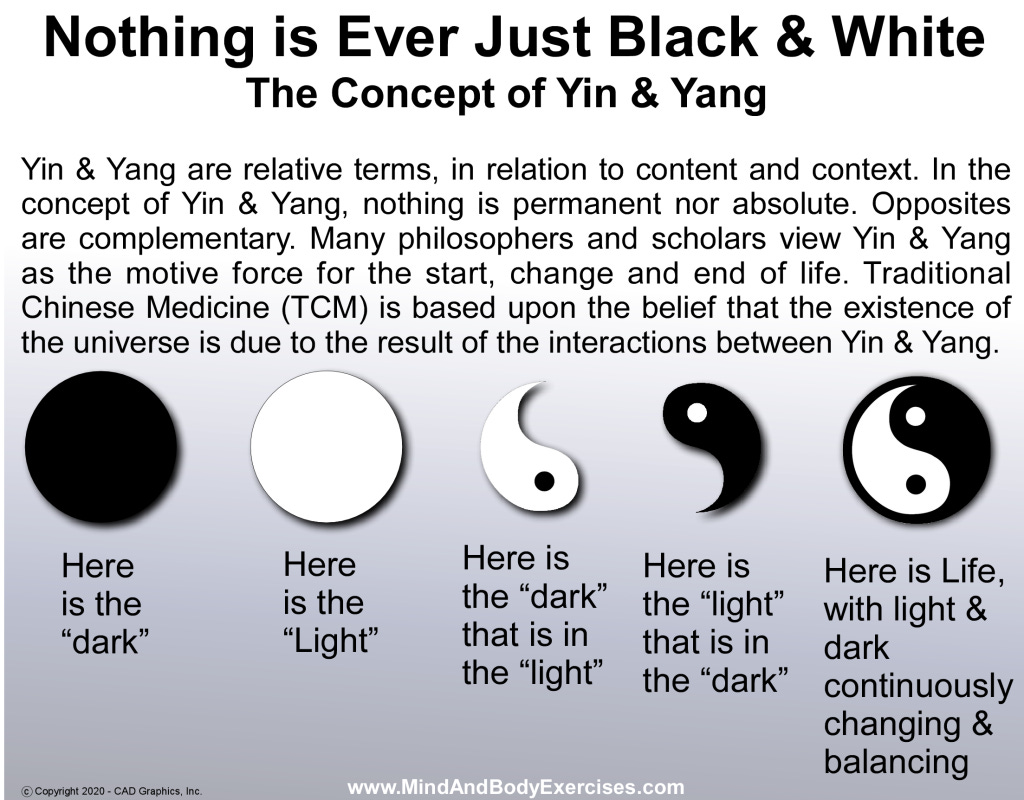

For the purpose of this post, we will be looking at Marxist dialectics (which are heavily influenced by Hegel). Rather than a conversation or the sequential thesis-antithesis-synthesis method which Kant put forth, Marx takes a dialectic (i.e. bourgeois and proletariat) and holds each aspect as dependent on and arising with its opposing aspect. They are like YinYang in this way, but where they differ is in their relationship. Whereas YinYang is based in complementarity, dialectics are based in contradiction. If this all sounds confusing, don’t worry; I will break it down further shortly.

In this analysis, I will explain why materialism and idealism, dialectics and YinYang, contradiction and complementarity are not mutually exclusive, and indeed understanding them as a totality (much like the Tao) is useful for understanding various aspects of our world. So let’s unpack. Here is verse #2 of Tao Te Ching in its entirety.2

Everybody on earth knowing that beauty is beautiful makes ugliness. Everybody knowing that goodness is good makes wickedness. For being and nonbeing arise together; hard and easy complete each other; high and low depend on each other; note and voice make the music together; before and after follow each other. That’s why the wise soul does without doing, teaches without talking. The things of this world exist, they are; you can’t refuse them. To bear and not to own; to act and not lay claim; to do the work and let it go: for just letting it go is what makes it stay.

One of my hesitations in abiding fully in Taoist philosophy is its emphasis on harmony in all things. It seems almost naive to think that war, climate exploitation, oppression, etc. could be harmonious. That’s why the historical materialism of Marxism appeals to me. His approach, to me, is better at explaining the ways that material contradictions arise and resolve, then morph into new contradictions.

For instance, the contradiction between slave and master resulted in conflict and tension that intensified until it reached a qualitative change in the relationship. From this, a slightly less exploitative but still unequal dialectic between lord and serf did the same thing, until we reached where we are now, the dialectic of capitalist and proletariat. Marx says that these contradictions are ever-evolving and progressing towards what he predicts will be Communism—a stateless, classless, moneyless society. Importantly, in Communism, all contradiction would not be resolved. Rather, contradictions would cease being class-centric and perhaps morph into something resembling existential contradictions about life and our purpose. Mao writes:

“There is internal contradiction in every single thing, hence its motion and development. Contradictoriness within a thing is the fundamental cause of its development, while its interrelations and interactions with other things are secondary causes.”

But where materialist dialectics (and Marxism as a whole) fall short, for me, are in elucidating concepts related to the mind, consciousness, ethics, ontology3, spirituality, and cosmology4. Marxism’s lack of guiding principles in these essential subjects has historically led to ego, conflict, infighting, and ineffectiveness in Marxist organizations. Joseph L. Pratt and Zhao Yingnan write in A Daoist Critique of Dialectics and Why It Matters, “Marx, though not concerned with ultimate reality, could not connect being, or physical form, to thought—the essential reflections on that being.” Verse #2 continues:

Everybody on earth knowing that beauty is beautiful makes ugliness. Everybody knowing that goodness is good makes wickedness.

Marxism may be a great way to examine history and politics, but what about these more abstract, ethereal concepts? Mao writes:

The universality or absoluteness of contradiction has a twofold meaning. One is that contradiction exists in the process of development of all things, and the other is that in the process of development of each thing a movement of opposites exists from beginning to end.

If goodness and wickedness contradict each other, in which direction are they moving? What about beauty and ugliness? What is the end point of these supposed contradictions? Perhaps I am missing something; please let me know if I am.

Rather than contradiction, Taoism operates under the principle of complementarity. This is best understood by examining the concept of YinYang.

YinYang is one of those concepts that many people have some understanding of, but few grasp the full scope of it. I am going to keep things pretty high-level, because it can get heady, but if you want to read more, I’d recommend the essay from which I will be quoting the rest of the way.5 Verse #2 continues:

For being and nonbeing arise together; hard and easy complete each other; high and low depend on each other; note and voice make the music together; before and after follow each other.

As the Huangdi Neijing explains, “in harmony the YinYang’s two aspects lean on, support, and attain each other.” The above verse represents these two aspects—being & nonbeing, hard & easy, high & low, note & voice, before & after—and how they each depend on and complete the other. They are not, as dialectics would suggest, moving towards some resolution, but instead they simply are.

Verse #42 of Tao Te Ching explores Yin-Yang as well, introducing numerical concepts which I’d like to discuss.

The Way [Tao] bears one. The one bears two. The two bear three. The three bear the ten thousand things. The ten thousand things carry the yin on their shoulders and hold in their arms the yang, whose interplay of energy makes harmony.

So, four numbers are given here, which Zhao and Pratt elaborate on. The sequence goes: Tao [0]6, One, YinYang Two, and Form Three. Each number depends on the subsequent and preceding number. Additionally, each aspect exists as either Yin or Yang in a pair. Tao (Yin) and One (Yang), YinYang Two (Yin) and Form Three (Yang). The numerical sequence continues so that all even numbers (0, 2, 4, etc.) are Yin asepcts, and all odd numbers (1, 3, 5, etc.) are Yang. Zhao and Pratt explain how the first four numbers would apply to the concept of change.

By way of explanation, the Dao could be considered the ultimate Changeless (or Eternal), while the One is the transcendent Change. At the level of YinYang Two-ness, the Yin aspect is the changeless and the Yang aspect is its counterpart, change. Finally, at the level of YinYang Two-ness and Form Three-ness, the YinYang Two-ness is the changeless component, though it encompasses both changelessness and change, and the Form Three-ness is the corresponding component of change. As with the circular and linear, both the changeless and change are necessary for the experience of the Dao.

You can think of YinYang (Two) as the conceptual or ideal, and Form (Three) as the manifest, concrete, or material. YinYang Two is energy, Form Three is matter. YinYang Two is emotion and Form Three is the expression of that emotion. YinYang Two is a musical chord and Form Three is the sound that chord makes when played. These two aspects lean on, support, and attain each other. You could not have energy without matter and you could not have matter without energy. An emotion necessarily produces some sort of expression, and said expression could not exist without the underlying emotion. So, rather than dialectical materialism, which rejects the ideal, YinYang contains the ideal and the material.

To accord with the Middle Way, these two components [Yin and Yang] must be in harmony and complement each other, achieving something greater than the sum of their distinguishable parts.

But back to my hesitation: how could YinYang complementarity explain antagonistic conflicts? If the universe supposedly exists in harmony, how can we explain poverty, revolution, violence?

My working theory is that humans exist in a period of disharmony; we have strayed far from the “Way,” and as such we are suffering for it. Pratt and Zhao describe this as a “discordant time,” a time of contradiction over complementarity, a time of power imbalance over harmony.

In a complementary state the YinYang aspects are said to complement, support, and attain each other, while in a contradictory phase the two sides contradict, chase, and deplete each other.

At the cosmic scale, humanity’s entire existence is a grain of sand, and the industrial age is perhaps an individual molecule within this grain of sand. I think that the Tao and its harmony and balance could be the true nature of reality. But right now? How could anyone say this is hamonious?

Complementarity allows for a return, first to the One as a “Whole” that is greater than the sum of the parts, and finally to the Dao as the ultimate reality. Contradiction, on the other hand, always falls short of this transcendent Whole, resulting in a continuous negative-sum outcome until a positive change occurs. Complementarity therefore is akin to the higher true or absolute, whereas contradiction is akin to the lower artifice or relative, which in a discordant time becomes a false, or mistaken, narrative of reality.

In Pratt and Zhao’s critique of dialectics, they focus almost entirely on what contradiction leads to within the individual mind. They say that a discordant state leads to insecurity and alienation from the self, but Marxism says that exploitation and capitalism leads to alienation from one’s labor and community.

As such, I think that Taoist philosophy is more valuable for understanding the self deeply, and bringing peace into the world. But dialectics can be useful for understanding society.

That’s why the wise soul does without doing, teaches without talking. The things of this world exist, they are; you can’t refuse them. To bear and not to own; to act and not lay claim; to do the work and let it go: for just letting it go is what makes it stay.

The verse concludes by presenting a way that wise souls can engage with the world to be in accordance with complementarity, harmony, the Tao. Effortless action, changeless change, transcendent wholeness. “The things in this world exist, they are.” Whatever your thoughts on dialectics or complementarity, you cannot refuse the way the world actually is. So go with its flow, find peace within yourself, and let your actions emanate from a place of tranquility.

In this post, I’ve laid out what I see as limitations of these schools of thought—Taoism/YinYang and Marxism/dialectics. YinYang is not useful for understanding material events of history, power dynamics, or societal conflict. And dialectics cannot explain ideals, cosmology, or consciousness. It is entirely possible that I’m wrong or misinterpreting. Apparently The Art of War is based on Taoist principles. Please, let’s have a discussion in the comments :)

Pratt and Zhao don’t see the value of dialectics in any form. They write, “Dialectical thinking, on the other hand, may dominate in a discordant state. Experiencing alienation and insecurity and under the influence of erratic impulses, people resort to one-sided thinking.”

I think they are missing the point. Dialectics are merely a tool. They are not the totality of reality, nor do they claim to be. Taoism perhaps does encompass totality, as it offers an explanation for the state of society—that we are living in a discordant time removed from the Way. But as we are living through this time, we need tools to understand it. That is where dialectics and historical materialism are valuable. Zhao and Pratt continue:

Crisis points, moreover, do not lead to progress, for the same reason that negation does not lead to a progression. For positive-sum change, there must be a harmonious balance between the consciousness-cognition and form. Only in this way can a higher state of the energy-matter dynamic and thus a true breakthrough be achieved. Extreme discord may lead to harmony, but only because people realize that the discord is counterproductive and turn to a harmonious approach as an alternative possibility. As already discussed, the Middle Way acts like a pivot, and the farther people deviate from it, the more they feel pulled back to it.

Again, I have to disagree with this notion. They say that extreme discord only leads to harmony because people realize discord is counterproductive and turn to harmony instead. Maybe this is true in some cases, but certainly not all. Revolutions have not succeeded because the oppressors and the oppressed decided to settle on harmony. They succeed because the masses forcibly take what is rightfully theirs.

The bourgeois are never going to capitulate because they feel that true harmony would be more productive. They may exist in a discordant state removed from the Way, and perhaps this is the reason they are alienated, but does that really matter? If we focus solely on harmony and following the Middle Way, would this not make us complacent as our rights are stripped away from us?

At the same time, as the authors point out, a focus on contradiction may limit our possibilities.

Focusing on the material and contradiction, Marx perhaps could not realize how his theoretical emphasis on contradiction confined himself and others to a degenerating state and that such an existence could never lead to a sustainable social arrangement.

I think this is a crucial point. I would consider myself a socialist, but I—along with most socialists—recognize its failures and shortcomings. Yes, the US is largely to blame for the brutal imperialism (economic and militaristic) that has stifled socialist projects from the USSR to Cuba to Chile to Venezuela to Guatemala and Nicaragua (to name just a few). But the fact of the matter is we have not been able, thus far, to “crack the code” and create a sustainable socialist project. Perhaps the authors have a point that Marx’s focus on contradiction and negation lead to regression, rather than the progression towards Communism that Marx had in mind.

But there is a reason why egomaniacal authoritarians end up in power. The people who crave power, the ones willing to sacrifice their humanity and dignity, are the ones who are capable of doing what it takes to seize, maintain, and expand said power. And Taoism, unlike Marxism, doesn’t provide a way of combatting this.

The authors say that “Marx was wrong to focus on discordant historical times, such as slavery, feudalism, and capitalism, and ignore concordant historical times.” They say that such times led to real progress because of their harmony. First off, how harmonious were these times, really? There was still exploitation, war, inequality, repression, etc. Is that just how things will always be? Can we not do better? Additionally, this statement ignores the fact that it is because of the masses demanding rights and fighting for their dignity that led to the more harmonious times.

I do agree, however, that “complementarity and contradiction are both part of phenomenal existence and have been integral parts of human evolution and history.” Despite living through a period of immense inequality, I still feel I have been able to find some level of harmony in studying the Tao, practicing mindfulness, educating myself, and doing work I feel good about.7 Perhaps this is the real takeaway.

So, I will present a new, complementary dialectic, or dialectic YinYang, if you will—between Dialectics and YinYang. Dialectical thinking to understand society, conflict, history, and power. YinYang to understand the mind, consciousness, nature, and balance. Dialectics to provoke, YinYang to transcend. These two aspects complement, depend on, and arise with each other. They are two parts of a holistic understanding of opposing forces.

As Daoism shows, [the experiential and trancendental] realms, or layers of reality, are seamless, and through the harmonious Middle Way, people can experience freedom even at the level of form. This freedom consists of people living in harmony with their surroundings, including with other people, and thereby experiencing the transcendent possibility reality offers. This freedom begins as an inner freedom but also acts as an outer freedom. When people accord with the Dao, the world accords with them […] In such a state, a secure logic is a faithful servant to an accurate intuition, and people know what they should do and are fulfilled in their pursuits. In the ideal state, the self and the other become a seamless whole.

Verse #55 of the Tao Te Ching says that “Whatever is contrary to Tao will not last long.”8 As I explained, our period of discord is unfathomably miniscule in the cosmic sense. So we can only hope that Lao Tzu is correct in asserting this. Finding the Tao within oneself is not individualistic; quite the opposite. It is a higher state of consciousness, a true freedom of soul and transcendence, and as you move closer to it, you move humanity closer to it as well.

This deep dive into verse #2 proved challenging, but incredibly rewarding. I am by no means an expert on dialectics, Marxism, or Taoism.9 So if you disagree or want to discuss further, I welcome that discourse in the comments. Thanks for reading <3

On Contradiction (1937) by Mao Tse-tung

Ursula K. Le Guin translation

This is not to suggest that Marx hasn’t written about ontology or the mind. But from what I’ve read it doesn’t really do it for me.

Spinoza, a forefather of dialectical materialism, has concepts that get into metaphysics and spirituality. I haven’t read him but will be looking to in the future.

A Daoist Critique of Dialectics and Why It Matters by Joseph Pratt and Zhao Yingnan

“The Dao might be considered an Absolute Zero or Circular Immediacy, or perhaps more conventionally as a fathomless “Here and Now.”” (Pratt & Zhao)

We cannot, however, overlook my immense privilege as a white man born to the richest country on earth. I have been afforded time and resources to go through the long and arduous process of finding some semblance of peace. Most do not have this ability. Which is why I feel Taoism cannot be the only answer.

Gia Fu-Feng translation

If you want to learn more about Marxism and dialectics, I recommend the podcast RevLeft radio. The host has a background in philosophy and does a great job explaining complex topics.

a dialectic approach certainly does help with understanding reality; as you’ve said, it’s a tool, albeit one that relies so heavily on distinction that it appears unattractive to the Daoist thinker.

by the same token, the Daoist thinker may be prone to inaction for the sake of inaction, rather than the “effortless action” of wuwei. they may be compelled to see and accept things as they are, leading to complacency.

in some sense, yes, we have to face reality and attempt to see its beauty, but on the other hand, we need to be aware of contradiction and conflict which are endemic to reality.

i see the opposites posed in the second verse as more or less related to the marxist dialectic or the master-slave relation, as laozi claims that those who see beauty as beautiful are engaging in ugliness. ugliness and beauty are subjective; they must simultaneously appear and self-reinforce. they do not exist in the One, and certainly not in that which spawns the One. there IS a contradiction, which the authors you cited seem to misplace.

i have been working (barely, lol) on a piece about the connections between anarchist thought and daoist thought. i have run into a similar situation; there is clear crossover, but it’s not possible to confidently proclaim anarchism as daoist, nor does daoism map onto anarchism neatly.

interestingly, there is a tendency of later daoists to appeal to the primitive times before heaven and earth were separated or lord and serf were installed into society. it seems they also believed we live in a post-harmony world.

That was fun to read, thank you. What drew me to the Daodejing as a philosophical, even primitively scientific document, is its refusal to set anything outside of Tao - or Nature - and pass judgment on it. War, evil, oppression, this is part of Nature as well as the opposites, and Nature is indifferent to it all. My reading may differ from others.