The first time I read chapter 3 of the Tao Te Ching, I was very confused. The wise ruler should “empty minds” and “weaken wills”? He should “keep people unknowing, unwanting”? Sounds like authoritarianism to me. But of couse, there is a larger point being made here. Let’s take a look:

Not praising the praiseworthy keeps people uncompetitive. Not prizing rare treasures keeps people from stealing. Not looking at the desirable keeps the mind quiet. So the wise soul governing people would empty their minds, fill their bellies, weaken their wishes, strengthen their bones, keep people unknowing, unwanting, keep the ones who do know from doing anything. When you do not-doing, nothing’s out of order.

I find it particularly valuable to examine the different translations of this verse. For instance, Gia-fu Feng’s phrase, “then clever people will not interfere,” gives us a clue to what Lao Tzu is getting at with his idea of emptying minds/hearts and keeping people unknowing. He is not saying that leaders should repress or coerce their citizens/followers into ignorance. Rather, he is saying that people are better off when they follow their true nature, the Middle Way. Cleverness & cunning are decidely removed from the Way. Leaders and followers alike would be wise to remember this. Verse #65 states: “Rulers who try to use cleverness / Cheat the country. / Those who rule without cleverness / Are a blessing to the land.”1

Not praising the praiseworthy keeps people uncompetitive. Not prizing rare treasures keeps people from stealing. Not looking at the desirable keeps the mind quiet.

In Buddhism, desire begets suffering. Our clinging to desire thus makes us suffer more. We desire wealth, material goods, career success, love, friendship, acceptance, admiration, respect, knowledge, wisdom. And if we achieve a certain desire, there is always another, greater desire. There is always someone doing better than us, more successful, more enlightened, more respected, with more friends, a better romantic life. So our cravings never cease; they only grow stronger and we grow more unhappy.

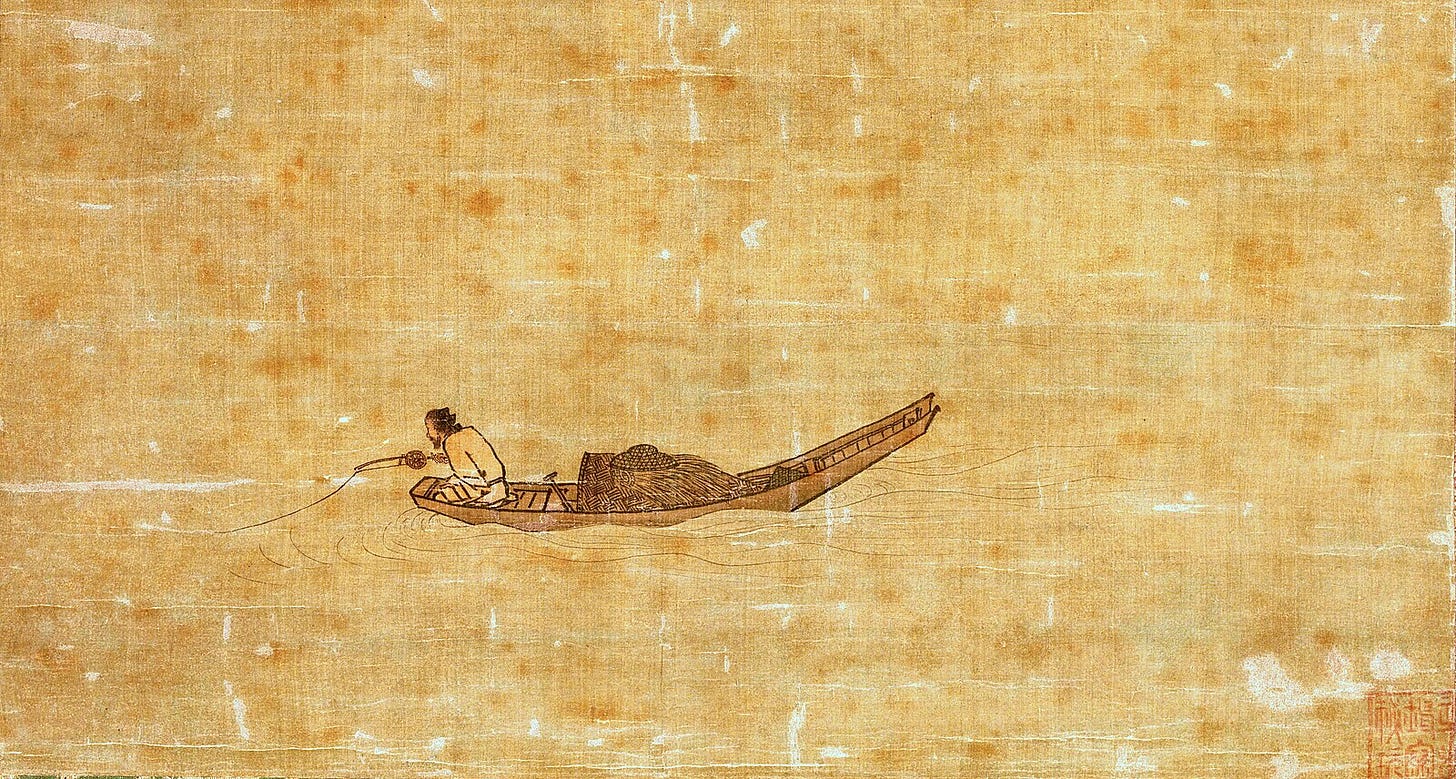

Lao Tzu’s approach to desire is one of emptiness, of absence. He says to not look at it. Put another way, this is non-action [wu wei]. Zhuanzi tells a story using emptiness [xu] to signify the emptying absence.

Bright Dazzlement [Guang Yau, literally ‘glowing light’] asked Nonexistence, ‘Sir, do you exist, or do you not exist?’ Unable to obtain any answer, Bright Dazzlement stared intently at the other’s face and form—all was vacuity and blankness [kong]. He stared all day but could see nothing, listened but could hear no sound, stretched out his hand but grasped nothing. ‘Perfect!’ exclaimed Bright Dazzlement. ‘Who can reach such perfection?’

Byung-Chul Han, in his book Absence, says that blankness and absencing are both central elements of Buddhism and Taoism.

Both Daoist and Buddhist thought distrust any substantive closedness that subsists, closes itself off, and perseveres. With regard to absencing, understood in an active sense, the Buddhist teaching of blankness, kong (空), is certainly related to Daoist emptiness, xu (虚). Both bring about an absencing heart, empty the self into a non-self, into a no one, into someone ‘nameless.’

He points to several examples in Far Eastern culture and thought to show how this tendency towards emptiness manifests—from the emptiness of food like soups and rice that take on the shape of their surroundings, to language, to how the sea is treated in Western vs. Eastern literature. It’s a fascinating read and I will be referencing it heavily in this series.

Zhuanzi says that “The Perfect Man uses his mind like a mirror, going after nothing, welcoming nothing, responding but not storing.” This is reminiscent of the meditation mantra of “let it come, let it be, let it go,” which describes how to respond to thought while meditating. Similarly, the empty mirror relates how one can respond to desire in a way that absences oneself from it, not suppressing but allowing to fall away.

In a state of absence, leadership arises from a place of wu wei, effortless action.

So the wise soul governing people would empty their minds, fill their bellies, weaken their wishes, strengthen their bones, keep people unknowing, unwanting, keep the ones who do know from doing anything.

The belly is a non-desiring organ in Taoist thought. It does not seek sensual pleasures, like that of the tongue and its “discriminating taste that strives for something specific.” Belly and bones are used figuritively here, “they are organs of in-difference.”2

The hypothetical wise leader in this verse is one that leads by example. He empties his mind of delusions and frees himself of wishes/desires so that his people might do the same. His bones are strong and belly is full with the potentiality of the Tao. His cleverness disippates into naturalness and he abides in non-action.

When you do not-doing, nothing’s out of order.

Le Guin had this to say in the notes for this chapter.

Over and over Lao Tzu says wei wu wei: Do not do. Doing not-doing. To act without acting. Action by inaction. You do nothing yet it gets done.

It’s not a statement susceptible to logical interpretation, or even to a syntactical translation into English; but it’s a concept that transforms thought radically, that changes minds. The whole book is both an explanation and a demonstration of it.

Or, as Byung-Cul Han says, Laozi and Zhuangzi’s project of Daesin [being human] “does without sense and goal, without teleology and narration, without transcendence and God. In it, the absence of sense and goal is not a deprivation; rather, it means greater freedom, a more coming from less. Only through dropping the walking-towards does walking actually become possible.”

This quote reminds me of the films of Japanese filmmaker Hayao Miyazaki, and his creative process. Rather than a screenplay, Miyazaki and his team start with storyboard, and they draw their way through the story before adding any dialogue. He studies plants and talks to children to get closer to something resembling an organic world that his films live in. It’s why his films often have deep meaning relating to the natural world and humans’ place in it, but it never feels forced. Pamela Gossin writes, “Art is not only an organic process for Miyazaki, it is a living being, an organism. He does not impose environmental views or ecological values upon his animation. He does not need to; his films are a natural part of who he is, what he thinks, believes, and breathes.”3

When one approaches the world through a place of receptivity, rather than activity, when they become water, the world then guides them through the valleys of life until they reach the sea, become one with it, and find their natural place within it.

Gia Fu-Feng translation

Absence by Byung-Chul Han

“Animated Nature: Aesthetics, Ethics, and Empathy in Miyazaki Hayao’s Ecophilosophy” by Pamela Gossin: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/mech.10.2015.0209

fantastic - it’s got me thinking about the focus on emptiness and the Nothing being something of transcendent perfection. it appears to be passive/feminine (Yin), but in reality is beyond such. it is not passive, not really. it is all-giving in its emptiness; it is the ultimate mirror, but for all forms and functions in the absence of light.

i find that by channeling this quality, life opens up before one’s eyes. one almost becomes animal-like. i sometimes like to imagine stumbling upon alien life, non-sentient, and observing it with no prior knowledge or assumption. watching as they act in ways unfamiliar, dying to understand how they think. then i wonder, if aliens were to find our planet, how they would view us. perhaps it is more elegant, beautiful to act as we may without meddling and greed. i would certainly like to see that beauty in a foreign world.