The record crackles as it begins to fade in. A distorted bassline and muffled voice gain clarity. Horns join the cacophony. A repeated line becomes understandable by the third or fourth repetition.

“Every n*gga is a star”

This iconic opening of Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly (2015) fittingly samples a 1973 Boris Gardiner track about blaxploitation, “Every N*gger is a Star,” whose album doubled as a soundtrack for a film of the same title. Calvin Lockhart, director of the film, had this to say about its signification.

“I think if we can understand what is actually going on, and control the economics of the situation we can really be bigger than we are at the moment […] If you own the means of production and distribution of production, then you control the thing and until we black United States actors can do just that; we can’t begin to talk about our conditions, or future in acting. We have to control it.”1

With this opening sample, Kendrick telegraphed the central theme of TPAB, his messy reckoning with the stardom that came from his breakout debut album, good kid, M.A.A.D. city (2013). Over the rest of the track, “Wesley’s Theory,” Kendrick would grapple with the intoxicating fame that GKMC brought, describing how his love for hip hop had warped into a lust for success, wealth, and status.

At first I did love you, but now I just wanna fuck.

“Wesley’s Theory” also features a guest verse from Uncle Sam, a character meant to represent greedy music industry who looks to exploit Kendrick’s talent (the “butterfly” in To Pimp a Butterfly) for its own profit. Uncle Sam encourages Kendrick’s consumption and flaunting, knowing it ultimately benefits him:

Because you make me live forever, baby / Count it all together, baby / Then hit the register and make me feel better, baby

I’ve already made an entire video on To Pimp a Butterfly, which you can watch below if you want further breakdown of the album, but it’s not necessary for this post.

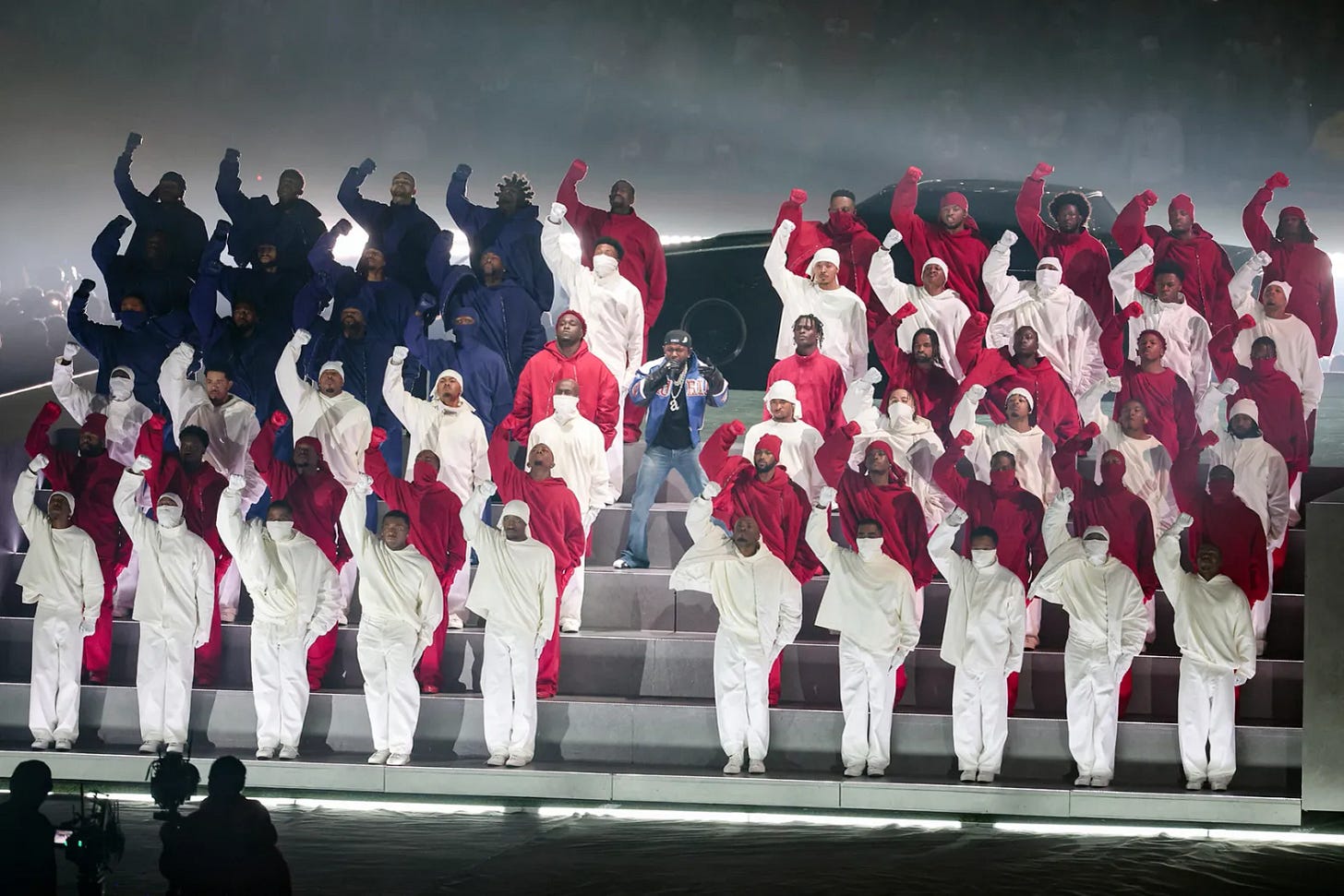

Fast forward ten years and here stands Kendrick, at the height of his fame, having defeated any pseudo-adversaries and proclaimed himself king of the rap game. And here he stands at the height of American capitalism and (symbolic) empire, the Super Bowl halftime show.

In many ways, the NFL is everything that Kendrick was criticizing on TPAB. It exploits its largely black athletes’ talent while raking in billions for its almost exclusively white owners and executives.

It platforms the American Dream with partner ads from Nike and Adidas about how anyone can “make it” if they work hard enough, messaging which supports a college and high school football industry in which millions of athletes sacrifice everything and put their bodies on the line, often with dire consequences, all for the miniscule possibility that they escape the shackles of systemic oppression.

It adds empty platitudes like “End Racism” to the backs of its endzones2, but blackballs athletes who show solidarity with black men murdered by the hands of police. It fetishizes the military industrial complex, monetizes patriotism, and supports the lifeblood of capitalist consumerism.

And that brings me to the paradox of Kendrick Lamar, the paradox of all of us living under capitalism. For all his semi-revolutionary rhetoric, Kendrick’s Super Bowl performance did very little to advance any radical message.

He played it safe.3

The reality is: what he did with storytelling and artistry (which I’ll get into) is about the farthest you can push the envelope as a Super Bowl performer. This is the paradox.

When Kendrick dropped To Pimp a Butterfly, he naively thought it would change the world. He thought, perhaps, that its message would unite his people under one banner and that the pain and trauma he experienced growing up in Compton would start to dissolve into love, solidarity, and peace.

“Sorry I didn’t change the world, my friend. / I was too busy building mine again.”

“Mirror” by Kendrick Lamar (2022)

Real change doesn’t happen so quickly. We still have a long way to go before any threat to this dystopian future we’re barrelling towards has enough mass support to pose a threat. Kendrick saw the culture’s reaction to what was widely considered a masterpiece and it wasn’t enough.

The result was DAMN. (2017) which delved into the darkness in his soul, and how he feels his people and humanity as a whole are damned by God. It’s my least favorite of his works, personally; I found all the Hebrew Israelite nonsense ridiculous and disappointing4. But I respect its honesty and it won a Pulitzer, which is both ironic and affirming, in different ways.

Lamar disappeared for five years to focus on himself and came back with a cathartic exploration of his inner grief, depression, and ultimately self-acceptance with Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers (2022), which though not as sonically interesting as his older works is incredible in its own right.5

Having put his demons to rest, we seem to be living in a new era of domination from the 37 year-old hip-hop purist who ran circles around and effectively destroyed the legacy of Drake this past summer. After the beef, we got GNX (2024), which to me was fun, though forgettable (by his standards). I can’t really hate on it though because he earned every bit of the right to fuck around on some dirty LA beats for a bit.

And that brings us to now, a Super Bowl halftime show which, like GNX, was very fun but predictably flew over the heads of White America, something Kendrick knew would happen and called out in the lyrics of the unreleased snippet at the beginning of the show.

You would not get the picture if I had to sit you for hours in front of the Louvre

Kendrick played a balancing act with his halftime performance, opting for symbolism over overt criticism. The interludes from Uncle Samuel L Jackson prove his self-awareness (notice his use of “the game”)

Salutations! It’s ya uncle, Sam. And this is the great American game!

No, no, no, no, noooo!! Too loud, too reckless, too… ghetto. Mr. Lamar, do you really know how to play the game? Then tighten up!

Kendrick is having a meta-conversation with the audience, telling us that he knows he has to make concessions as a black entertainer operating in a white industry. “The game” can represent the American Dream, but also the game that he has to play to continue his meteoric rise and platform the plight of his people.

This is the inescapable paradox of anyone working towards change in our world. The same exploitation that Kendrick criticized way back in 2015 he feels he has to capitulate to now.

It’s a similar phenomenon to Hollywood films “criticizing” capitalism. They are happy to make vapid platitudes about the rich, as long as the focus is on individuals and not the inherent violence and injustice in the system itself. Similarly, the NFL is happy to platform black culture that is critical of capitalism and white supremacy, and write “End Racism” in its endzones, as long as they don’t have to make any meaningful strides towards anything that might actually make a difference.

After Kendrick brings SZA out (who crushed it btw) to perform “luther” and “All the Stars,” Uncle Samuel L Jackson comes back in and says.

Yeah! That’s what I’m talking about. That’s what America wants. Nice and calm. We’re almost there, don’t mess this u—

This is of course more loaded language, a commentary on how America wants black people to act—nice and calm. “Not Like Us” is thus a direct response to America, as much of a fuck you as would be tolerated. You, America6, are not like us, the culture. Yes, this is a Drake diss track. But it’s a diss moreso to what Drake represents, a disrespect for hip hop and black people. And if you don’t like it, you can “turn this TV off.”7

Side note: shoutout to the absolute legend in Kendrick’s dance crew that waved the Palestine/Sudan flag, which the cameras of course never showed.

What the Paradox of Kendrick Lamar represents, to me, is the contradiction running through all our lives and society. The contradiction between an oligarchy whose oppression is ramping up to 1000 and the restistance that it gives rise to. Between the internal conditioning towards self-exploitation and the realization of a better way to treat ourselves. Between mindless consumption and mindful education. Between individualism and community.8

At the end of the day, while Kendrick is insanely talented and insightful, he is not going to save us, as much as he’d like to, and we shouldn’t place him on a pedestal of infallability. He is a human like any of us, and though he’s constantly contradicting his “I am not your savior” line, I think this line is really where the truth is.

I did not make much of an effort to criticize Kendrick in my TPAB video above, and I think it suffers for this. Some comments have said that my solution of mindfulness and self-love as a means of escaping what I called the “staircase of ambition” was too individualistic. I’m not one to put too much stock into YouTube comments, but the majority of them were made in good faith, and as I thought about it, I realized they are right. A lot of Kendrick’s approach to change is individualistic. However, there is truth to some aspects of the type of individualism he advocates. There’s something to be said for healing yourself to heal humanity. We are all interconnected, even at the cosmic level, and you’re not doing the world any favors by trying to change it before you change yourself.

I think if I had to re-phrase my conclusion, I would say that whatever you do to educate yourself or build solidarity, it’s important that it emanate from a place of mindfulness. In Vita Contemplativa, Byung Chul-Han criticizes the concept of action itself, which he says paradoxically has its core in passivity.

The Anthropocene is the result of total submission of nature to human action. Nature loses all independence and dignity. It is reduced to a part of, an appendix, to human history […] We make history, by acting, and now we make nature by dissolving it into the contexts created by human action. The Anthropocene marks the precise moment that nature is completely absorbed into and exploited by human action.

Does he then think we should do nothing to stem the tide of climate catastrophe? No, he’s not delusional.

But if the cause of the impending disaster is the view that what is absolutely fundamental is human action—action that has ruthlessly appropriated and exploited nature—then we require a corrective to human action itself. We must therefore increase the proportion of action that is contemplative, that is, to ensure that action is enriched by reflection.

What does this mean in practice? It means less frenzied activity and more thoughtful engagement. It means tying back every social upheaval—Black Lives Matter, Occupy Wall Street, Palestinian solidarity, Women’s rights, labor, the Arab Spring, immigrant rights, hell even “free luigi”—into the same underlying systems that create them, global capitalism and American imperialism. It’s great that much of the general populous realizes the injustices these movements pointed out, but it’s not going to change anything until they all coalesce under one movement.

Byron Balfour, “Calvin Lockhart Plans to Do More Films Here,” Kingston Gleaner, May 18, 1974.

Yes, I know they just made the decision to end this in order to appease Trump.

For some reason, this offended someone coming from YouTube. To be clear, I am not saying that he should have done anything differently. That’s the whole point; that option doesn’t exist because if he did do something truly radical they would not have allowed him to perform it.

I respect anyone’s religious faith. What I don’t have respect for is people who think that the only way for us to not be “cursed” is for everyone to follow their religion/dogma/way of life.

The new Dissect season on this album just started, which I am very excited about. Check it out here.

In this context, I mean the particular strain of American exceptionalism and white supremacy, and the dominant ruling class that exploits minorities, immigrants, and developing countries.

Probably worth turning off the way the game was going anyway.

I’ve been reading a lot about dialectics, can you tell?