The Dark Colonial Past and Future of Psychedelics

The "psychedelic renaissance" is on a dangerous trajectory

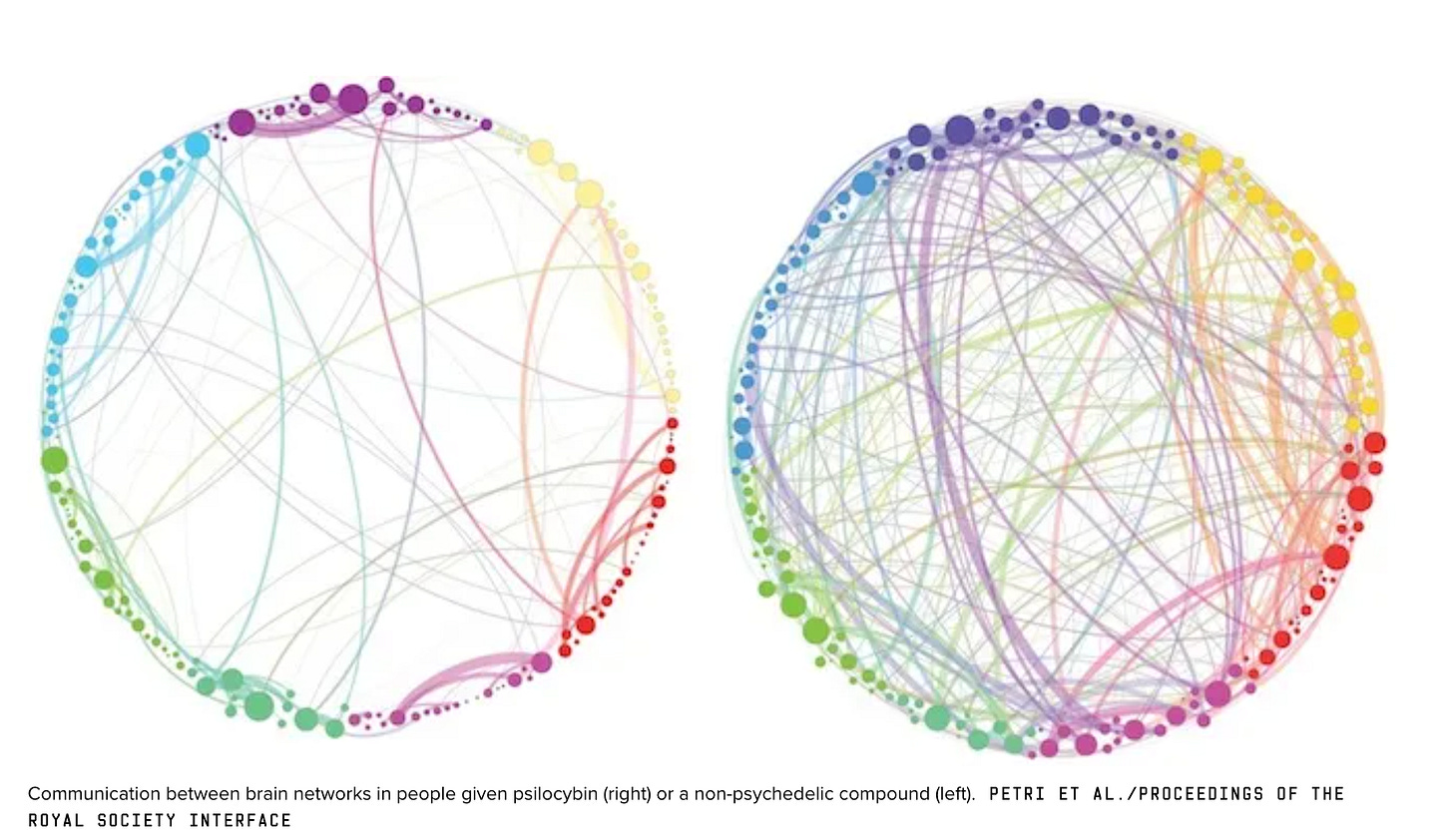

There is a common aphorism in the psychedelic community—that psychedelics “shake out the cobwebs” in your mind, breaking it free of its patterns, its rigidity, allowing new neural links to be formed. They freshen your perspective and remove you from the egoic enslavement to desire and the whims of your survival instincts.

The science behind these claims—which Michael Pollan’s How to Change Your Mind: The New Science of Psychedelics explores in depth—is legit. The below image visualizes brain activity before and after taking psilocybin.

And it's not just during psychedelic experiences; experiments and user testimonies have shown the effects are lasting. The reformation of neural pathways can have profound effects for treating depression, anxiety, addiction, grief, and a slew of other mental health syndromes. In fact, the evidence seems to suggest that psychedelics could be the future of mental health treatment.

But…it's not all sunshine and rainbows.

The western world was introduced to psychoactive mushrooms by way of Maria Sabina, a humble Indigenous Mazatec who lived in a remote village in Southern Mexico. Sabina was revered as a curandera (healer/shaman) in her village, whose services were used by the community for the purposes of healing and solving problems (such as locating lost love ones).1

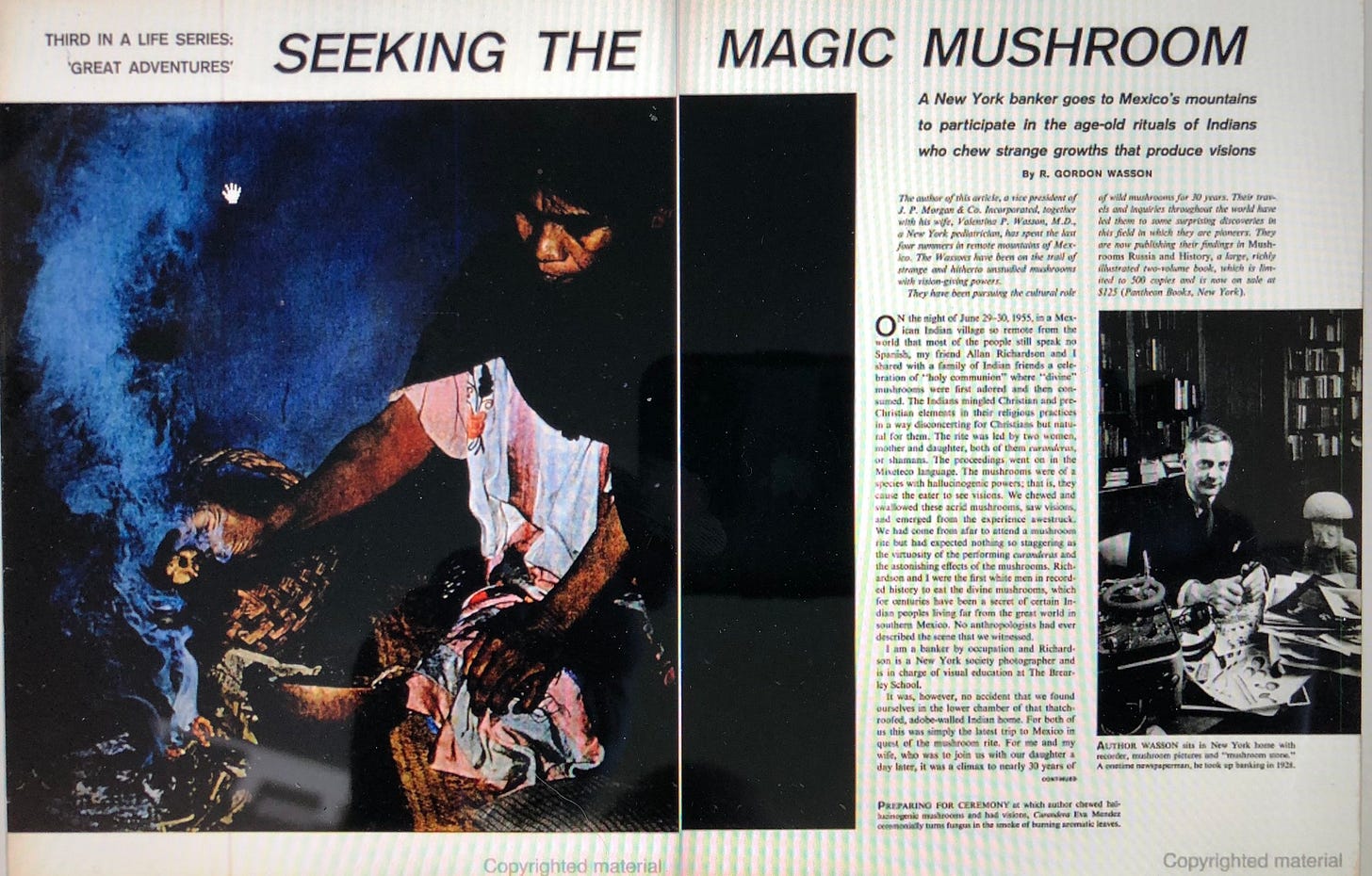

The vessel for Sabina’s story was one Gordon Wasson, a JP Morgan banker who fancied himself an explorer in his free time. On his travels, Wasson became obsessed with the Mazatecs' sacred mushroom rituals and sought to leverage the power of the psychoactive mushrooms for the purposes of study and science. Wasson’s first mushroom experience with Sabina was the culmination of 11 trips and 25 years of research and fieldwork.

But in his determination to experience the Mazatec mushroom ritual, which was sparsely documented and less understood in the west, he lied to Maria Sabina. Wasson falsely claimed that his son was missing and he wished to ascertain information on his whereabouts (a common curandera service). For this reason, Sabina agreed to guide him on a mushroom journey, and allowed his photographer to capture the experience. Wasson would publish his famous Life magazine piece, "Seeking the Magic Mushroom," shortly thereafter.2

But this ethical misdeed was not the only shady tactic employed by Wasson and his crew. While Wasson substituted her name for an alias in the Life article, later publications of his psychedelic experiences included her name, and the name of her village, making it easy for anyone who wished, to find her. Further, hearing the hype of the mushrooms that allow you to "touch god," the CIA sent an operative on a trip to Huautla to investigate whether these mushrooms could be used for mind control; this operation was part of the infamous MKUltra program, which went further with LSD, causing death and permanent psychological damage in many of its subjects.

It is worth highlighting the power dynamic here. Wasson, with his abundant resources, connected with the municipal trustee of Huautla, who then pressured Sabina to perform the ceremony for Wasson. She felt she had no choice. "I should have said no," she would later say.

Wasson’s 1957 story in Life Magazine blew up, and the subsequent events became one of many case studies which exhibit the arrogance, disrespect, and hypocrisy of white people in the neocolonial world. Counter-culture hippies who’d read the story and wanted to have their minds blown pilgrimed to Mexico in droves, in what would become known as the “hippie invasion” or “beatnik invasion.” They trampled sacred lands and disrespected the Mazatec customs and culture, all in search of some transcendent experience, a “searching for God” that fundamentally did not understand the ceremony. Further, overharvesting of mushrooms and continual harassment by Mexican authorities caused hardship in Sabina’s community for years to come.3

Sabina’s Mazatec tribe grew to resent her for unintentionally bringing this invasion on their people. She was exiled from her village, her home was burned down, and her son was murdered. Further, the Mazatecs’ sacred mushroom rituals were forced underground due to intervention from the Mexican military. In exile, Sabina suffered from malnourishment and poverty, a far cry from her prior reverence as a sabia, shaman, and poet. Sabina eventually expressed regret for her interactions with Wasson, not for any negative impacts on herself, but for the hardship it brought on her community. She was allowed to return home in 1987, and she would die in November of that year.

Maria Sabina’s tragic story is all too common in the imperialist, white supremacist world. If you hear this story and think, oh but that was so long ago. Surely we’ve learned from these mistakes, you’d be wrong.

Much like pure colonial occupation has transformed into the more subtle, less visible economic imperialism, so too is the present-day “psychedelic renaissance” on a dangerous trajectory to do the same. The commodification and exploitation of psychedelics is not new: the same exact thing happened with substances like tobacco, cannabis, and alcohol. All these substances were used in sacred ceremonies by indigenous peoples across the Americas, yet they had no substance abuse issues or health complications. Now we have lung cancer, heart disease, liver disease, and addiction. The people who suffer from capitalization are not only the indigenous peoples whose culture is commodified, but westerners who fall prey to the unhealthy habits formed by using these substances in the wrong setting.

The "psychedelic renaissance" is unique in that the potential of these medicines is undeniable. But it’s also not unique. It is merely another chapter in the storied history of selfish, pseudo-revolutionary hypocrites who don’t understand the history of these compounds, nor do they care to learn.

I know this because I was one of these hypocrites in my early 20s.

My foray into psychedelics began in earnest when I moved to Denver in 2022, though the seeds had been planted with previous profound, if slightly unnerving, experiences with LSD and psilocybin mushrooms. I had used them only a handful of times, with a friend at City Park in New Orleans and at music festivals a couple times. One experience in particular involved an emotional breakdown in a porta-potty during a Phish show at Bonnaroo 2018 (yeah, I know). I learned a lot from this trip, but I was so shaken by its intensity that I stayed away from psychedelics for four years.

The two years following this experience were the worst of my life, for unrelated reasons that I don’t need to get into here (in short: chronic pain, depression, loneliness, etc). The beginning of my healing came when I accepted help and sought therapy in 2020, and subsequently quit my job to travel across the US for three months, live out of my car, and experience the wonders of nature.

Psychedelics may have changed my life, but what healed me was therapy, self-care, and the great outdoors.

I began to come back around to the idea of psychedelics when I read How to Change Your Mind in late 2021. The subjects of the book who took these medicines described their experiences as deeply spiritual, cathartic, and life-altering. They described an underlying reality that is more true than what our waking consciousness experiences. They described ego dissolution, open-heartedness, and a profound sense of peace and love that permeates our universe.

I became enthralled by the myriad of stories like the ones in How to Change Your Mind. I watched documentaries, lectures, interviews, read more books, browsed subreddits, scrolled through psychedelic forums. The energy was palpable and I wanted to experience it for myself. But I didn’t want a repeat of the Bonnaroo porta-potty situation.

As I read and learned about psychedelics, one factor became apparent in what set apart a good trip from a “bad” one. Respect.

Psychedelics have become mainstream at this point. We got Aaron Rodgers talking about ayahuasca on Joe Rogan's podcast, tech CEOs going on psychedelic retreats, the dude from VSauce making a video about Ayauhasca. Some people are engaging with these substances in good faith and respect, but many are not. Many are repeating the same cultural colonization that the hippie invasion inflicted on the Mazatecs in the 1960s.

The psychedelic therapy industry is uniquely dangerous because the people who seek healing experiences are often at their most vulnerable, and have not put the appropriate thought into what they hope to accomplish and how. Maria Sabina’s people used psilocybin mushrooms for very specific use cases—primarily to cure sickness and solve problems. The curandera would commune with the spirit world using the “saint children” (mushrooms) and seek answers on how to heal their patient or find their loved one. But the hippies saw this and took it to mean that if they take mushrooms, they could touch God.

This video from Vice shows just how predatory and exploitative this industry becomes when so much money is on the line.

In learning about all of this and preparing for a new journey with mushrooms, I made a commitment: to always show respect to the people who sacrificed for introducing us to the “saint children,” and to always embark on a mushroom journey with a clear intention and mindfulness. I won’t pretend that I have been perfect along the way, and I also won’t pretend to know that my way is appropriate in the eyes of indigenous people. I can only speak to doing what felt right.

My first mushroom experience in four years was revelatory and indescribable. At the risk of sounding like a cliche, the whole of my consciousness was love, and the underlying structure of the universe was harmony. Waterfalls of emotion poured from my heart to my soul, and my body pulsed with euphoric waves of compassion for all life, myself notwithstanding.

Some people like to sneer or roll their eyes at these anecdotes (maybe you, dear reader, are doing so right now); they say it was just neurochemicals playing tricks on me. And I understand that, but I don’t think so. I believe there is something pure and eternal guiding our universe, and though we humans are stubbornly resisting in a discordant state of conflict and contradiction, if we simply embrace nature, all will be well. If you've been following along with my Tao Te Ching readalong, you may understand how its ideas correspond with my psychedelic journey. There is something magical about a substance grown from the earth reuniting us with it. You see the interconnectedness of all things, and if used with respect, psychedelics can teach you about yourself and reality.

You don’t need psychedelics to “wake up” to the world, to know yourself at a deep and profound level. I think meditation is a means to achieve similar ends using only the power of the mind. In fact, my biggest growth has come at times when I am not using psychedelics. But I do believe that the period of frequent psilocybin usage, from 2022-24, gave my brain the shake-up of my habitual complacency that it so desperately needed.

The corporatization of psychedelics and the commodification of the mental health crisis are already in full swing. Oregon and Colorado, which voted to legalize psilocybin-assisted therapy, have opened their first psilocybin therapy centers, charging anywhere from $1,000 to $15,000 per "journey". The service, of course, is not covered by insurance, and even if it was, the reality of US health insurance is that the people who need it most are forced to live without it.

As a result of the exorbitant fees, many people are likely to turn to self-guided or unlicensed black-market guided therapy sessions. And with the general lasseiz-faire cultural attitude towards psychedelics, this can result in dangerous outcomes for inexperienced users who don't do their research and don't respect the powerful substances.

The simple fact is that most psychedelic users, whether recreational or therapeutic, are not aware of these dangers, much less about the cultural colonization that the "psychedelic renaissance" is built on. This ignorance is driven by the larger capitalist trend towards fetishism, the removing of context and making invisible the knowledge, labor, tradition, and wisdom that goes into production of commodities.

So is there a right way to use psychedelics? What would that look like?

The first thing I will say is that while I will present my thoughts, my perspective on this is not as valuable as indigenous voices who have been dealing with these questions more earnestly and for longer than I. Unfortunately, the valid concerns and hard questions such voices put forth are often met with resistance, defensiveness, ignorance, and refusal to actually listen. I will give an example from the MAPS Psychedelic Science Conference in 2023.

At this conference, self-described as "the largest psychedelic conference in history," the keynote speech was interrupted by a series of protestors, who were allowed to come on stage and say a few words each. Their concerns were similar to those I've laid out in this post. Angela Beers, a visiting instructor at Naropa University, said, “Nobody owns healing, you don’t own our culture. You can’t take it from us. We deserve respect. Where are the investors investing in land back, water rights?”

Jayson Paulino, a New York-based, Black and Indigenous educator and creative director of Black Girls Smoke, described a failure of psychedelic science and policy to consider the needs of people of color. “I come from the ‘hood,” he said. “People in the hood don’t get the healing they need. They can’t afford even to attend this kind of conference. We’re the ones that need to be here, we’re the ones that need the healing.”

Kuthoomi Castro, a Meztizo-Indigenous wellness professional originally from Ecuador, said, “It’s not just the medicines but it’s our intellectual property. People are taking our songs, ceremonies, rattles, our beautiful instruments, our relationship to nature, they’re taking everything…Some people are doing it right and beautifully, but the majority of people in the movement are messing things up.”

There were a few others which you can read about here, but the point is, these are specific and actionable issues that the protestors have with MAPS and the larger psychedelic movement. GA tickets for the conference start at $800 and there is nowhere near enough indigenous representation on the panels.

Yet, when a video of the protest was posted to Reddit, the top upvoted comments say things like "There wasn’t a single logical thought presented between the speakers, just pathos and ethos about wanting to be heard," or this comment and its reply praising MAPS inclusiveness and completely misunderstanding the protesters' points, thinking that they were trying to prevent any sort of usage of psychedelics by western users.

There were plenty of folks who chimed in to provide context as to what the protest was actually about, but these comments are downvoted and buried at the bottom of the thread. I could go on a whole tangent about how the 'like' or vote-based comment sections of Reddit, YouTube, TikTok, etc. are making us more ignorant and less critical, not to mention Reddit being dominated by culturally hegemonic straight white men, but that’s a topic for another time. To be clear, I don't think these comments are an accurate representation of the psychedelic community as a whole. In fact, I would argue that although sometimes ignorant, the majority of people I've met in the real world (through the Colorado Mycological Society and Telluride Mushroom Festival) are open-minded and willing to learn. But that doesn't mean there aren't diversity & representation problems.

As Jayson Paulino pointed out, the high barrier to entry removes those who need healing the most, people from the hood, as he said. This is a larger socio-economic issue, but it's one that the psychedelic community does not adequately address. A video I watched in researching this piece presents the argument that anti-racism must be a central tenet of the psychedelic movement.

In the video, four members of Chacruna’s Racial Equity and Access Committee debunk myths that because psychedelics are "mind-expanding," they are inherently "post-racial" or not political. The reality is, everything is political and racial, because that is the foundation of white supremacy. Buchanan says, "to define yourself as being outside of politics generally just means that you have bought into politics to the extent that they benefit you, and you're ignoring the way in which they don't benefit others...neutrality is a political stance." She points to the fact that although people of color are the global majority, psychedelic trials are designed and led primarily by white people, for white people.

There is also the myth that psychedelics on their own are enough to heal the world or cure racism, sexism, misogyny, classism, etc. This is obvious bullshit debunked by the fact that the worst people in the world--tech CEOs and VCs--are having a lil moment with psychedelics and are just as bigoted as they were before. Thinking psychedelics without proper education will heal is a dangerous myth, especially when people are using them to self-treat mental health problems.

In their paper Indigenous Philosophies and the "Psychedelic Renaissance",4 several researchers present some realistic, actionable ways in which to reorient our approach to psychedelic usage to be more inclusive of Indigenous perspectives. They write, "Please slow down and take the time to consider our relationships with plant and fungi medicines deeply." Australian Indigenous knowledge keeper, Tyson Yunkaporta, and Murruwarri Elder, Doris Shillingsworth, suggest the following for being "relationally responsive."

There is a simple process for your practice…It’s the order in which you do things properly. Respect, connect, reflect, direct. It’s a protocol for how you come into relation with a place or any kind of relationship you want to form. […]

If the so-called "psychedelic renaissance" unfolds like everything else does in this neoliberal extractive capitalist environment, individuals, families, communities, and even the planet will miss opportunities for healing.

The paper gives several more examples for decision making in psychedelic policy, including investment in land-back initiatives, inclusion of Indigenous leaders in decision making, establishment of Indigenous ethics watch organizations, and re-examining intellectual property rights (IPR) regarding Indigenous knowledge. If you are at all involved with psychedelic policy making, I'd highly recommend reading the whole paper.

For the rest of us, one strategy that the Chacruna video recommends is to use psychedelics to unpack our social conditioning. Dr. Buchanan says:

Our socialization is very difficult to overcome, and it doesn't get overcome because we took a substance 1 or 2 times without it specifically being our intention to heal the ways we've been pathologically socialized to believe in superiority and inferiority of other human beings.

People love easy answers and quick fixes. Trump succeeds because, among other reasons, he gives people simplistic scapegoats for their problems. Immigrants, DEI initiatives and China are to blame for our problems with underemployment, housing, health care, crime, etc. This scapegoating works because the real reasons for these problems are much more complex and nuanced.

Just the same, the reasons for your problems, whatever they may be, are layered and difficult to unpack. It requires work, and psychedelics can be a tool to help you in the process, but they will not heal you or solve your problems on their own. What they can do, if used correctly, is unite you with the interconnectedness of the natural world and foster solidarity with your fellow humans.

Indigenous traditions and philosophies, even if you don't literally "believe" in their spirituality, provide a compelling way of seeing the natural world. "In Mexico," Williams and Romero write,5 "the nomenclature associate with psychoactive mushrooms in the genus Psilocybe suggests a recognition of their personhood." Their words for various mushrooms can be translated as, "rainwater child," "sacred mushroom that paints or describes," "little saints," and "saint children." The land, too, is considered to be literally alive. In Nahuatl villages, "The people say that the soil is the earth’s flesh, the stones its bones, and the water its blood." The agency and sentience of non-humans is central to Indigenous philosophies.

I think we can learn from this perspective. If mushrooms are sentient, perhaps its best we commune with them, rather than use them. If plants are teachers, perhaps we should listen to what they say. If forests think, perhaps we should respect their thoughts. If rivers are people, perhaps we should allow them bodily autonomy.

My point in writing this piece is not to say that you must apply the indigenous framework of psychedelics to your experiences. It is not to say that psychedelics cannot be enjoyed in the recreational context. And it's definitely not to downplay the positive impact that psychedelics can have on our mental health crisis; quite the opposite. I recognize how beneficial they were for me, but these benefits came only when I was mindful and intentional with my usage.

Our future with psychedelics will be determined by how we respond to concerns about their commodification. Like tobacco, cannabis, and alcohol, there's a strong chance that the runaway train of capitalism will turn them into nothing more than drugs to be abused as an escape from the shitty world capital has built. But we, the people, have the power to change this. Educate yourself, support land-back initiatives & intellectual property rights. Allow Indigenous intellectuals and spiritual leaders to lead and advise the current practice and the future of psychedelics. Insist on “historical reparations” for the expropriation of mushrooms from Indigenous communities, as Mazatec researcher Osiris García Cerqueda has proposed.

The most concrete of these solutions—land-back, water rights, IP rights, historical reparations—are decidedly opposed to the capital interests which hold power over policy. How we respond to these demands will be telling. Is the system so inherently broken that we can't do right by the exploited and oppressed? Is any solution that maintain a profit motive and capitalist power structure doomed to fail? And if so, what does that say about our future?

same as above

my psychedelic craze started in the summer of 2014, lasting for a year or so. i loved shrooms. still do! but i don’t really use them anymore. there’s no need. they helped give me the strength to dive deep into myself and my woes; without them, i’m not sure if i would have beaten my anxiety and depression so adequately.

i didn’t know about the background of it all; thank you for sharing the history.

"One experience in particular involved an emotional breakdown in a porta-potty during a Phish show at Bonnaroo 2018 (yeah, I know)." - Who hasn't been there, right?? 🙏